Disadvantaged children in Eastern Europe have captured the artistic attention and personal commitment of painter Nick Kosciuk

August 8, 2017

Paulina, Olya, Anastasia, Natasha. When Nick Kosciuk hears the children’s stories, they always touch his heart—their mothers and fathers abandoned them in orphanages in Belarus, a republic near Russia, to be raised by strangers. The California painter recently returned from his 12th trip to Belarus in four years, bringing back with him not only the tales of orphans from this far-off land but also 2,000 photographs that will serve as reference material for his hauntingly beautiful portraits.

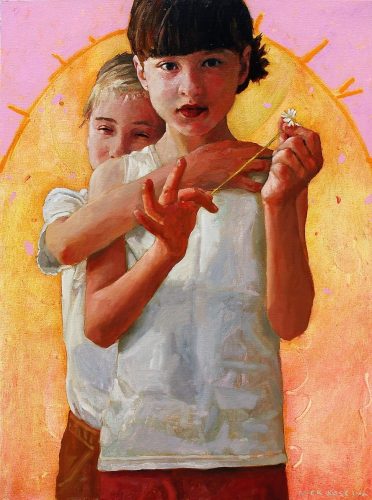

Faces of the Belarusian children stare out from Kosciuk’s starkly dramatic canvases, evoking a sense of mystery and the feeling that they have something compelling to say. Some have halos circling their heads, giving them an angelic countenance. Others wrap their arms around each other as if for support. All of their gazes are solemn and serene, innocent but knowing.

One day in December, Kosciuk reflects on his recent trip to Belarus from his studio at home in Cambria, a coastal town in central California. In his left hand, he holds a photograph of one of the children, 11-year-old Olya. In his right hand, he wields a paintbrush, with which he is re-creating the young girl’s likeness. Olya’s mother had kicked her out of the house and told the girl that she was no longer her daughter, Kosciuk recalls. “She told me the story with a smile on her face,” he says, noting that the children talk about their parents’ neglect and, frequently, alcoholism with the same casualness that children in America talk about their parents’ jobs.

He remembers shooting Olya’s photograph a few weeks earlier, asking her to write something silly on a green chalkboard and then lean up against it. The girl spontaneously wrote a letter to her mother: “If you love me, I will love you,” she inscribed. Kosciuk says that he was taken aback by the direct, matter-of-fact nature of the girl’s plea. “People may see this painting and say, ‘No way could this be true, could she have really written that,’” he says. “But it is true. I didn’t prompt her.”

Other works in progress are scattered throughout his house, hanging on walls, resting on mantels, and stashed in corners. His painting life spills over into his everyday life, and he is the first to admit that there is little separation. The 41-year-old is divorced, and his two children visit regularly, hanging out in his studio to watch him paint or watch a DVD. Emily, 15, has knit scarves for the children in Belarus, and Calvin, 13, has shared some of his savings. For the first time, Kosciuk plans to take his children on a trip to Belarus in early 2006. “This is better than any kind of sports league for them,” he says. “It will ground them and give them a good perspective on life.”

The Republic of Belarus is a landlocked nation-state in Eastern Europe that officially declared its independence in 1991 following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Because of allegations of human-rights violations, among other issues, the country has been excluded from joining the Council of Europe, an organization of more than 40 member states with the mission of facilitating economic and social progress.

After returning from each trip to Belarus, Kosciuk buries himself in his studio and paints with a near-religious fervor, creating a new series of works spotlighting the orphans. When each series is completed, the portraits are exhibited at The Vault Gallery in Cambria. Soon after, Kosciuk boards a plane for Belarus and begins the cycle anew. He takes with him a generous portion of the proceeds from art sales and donates it to several orphanages. He gives with no strings attached. “I’m not trying to change them, convert them, or tell them how to spend the money,” he says.

When Kosciuk arrives in Belarus, he usually spends about six weeks with the children, doing everything from playing silly games to taking walks to buy ice cream. And he snaps thousands of photographs with his digital camera. The younger children vie for face time, he says. Taking their photographs gives them time and attention, a very basic need for children. “The tiniest things seem to make such a huge difference in their lives,” Kosciuk says.

But why these children? Why does he travel halfway around the globe to find subjects to paint and institutions to which he donates his money?

To understand how Kosciuk became so involved in this effort, it’s necessary to go back in time, first a few years and then to an era before he was born. In 2001, he was at a low point in his personal life, the artist recalls. His parents asked him to accompany them on a trip to Belarus to explore the family’s roots. Kosciuk’s father was born there, and his mother, who was born in a German labor camp after World War II, is also Belarusian. They emigrated to the United States in 1950, married, and settled in South River, NJ, home to a tight-knit Belarusian community. His parents worked hard—his father in a factory and his mother as a waitress and maid. As a child, Kosciuk wasn’t too interested in his ethnic identity. “I just wanted to be an American,” he recalls.

That would soon change. Once Kosciuk and his parents arrived in Belarus, the stories he had heard as a child from his grandparents came alive for the first time. He met distant relatives and visited the site where his grandparents’ house stood before it was burned to the ground during World War II. He also retraced some of the steps the family took when they fled the country—his grandfather was ordered to the Russian front and refused to fight because he believed “Stalin was more evil than Hitler.” Kosciuk saw the road his grandparents traveled to escape, reliving their tales of how Russian soldiers pursued them and how they eventually were declared political refugees and transported to German labor camps.

But it was on the last day of his trip that he had an epiphany, Kosciuk says. A family friend, who was a linguistics professor, took him to visit a nearby orphanage in Rudensk. She usually visited once a week to offer the children Bible study classes. What he witnessed at the orphanage moved him deeply. “I saw so many kids with such a need for love and attention,” he recalls. “They were hanging on me. It hit me that there wasn’t a long line of people waiting to take my place and give them attention. I was it.”

Although he says that conditions have improved since then, Kosciuk’s first impression of the orphanage was that it was bleak, austere, and depressing. “I was there an hour or so,” he says. “In that time, I made a decision that I would come back for the rest of my life.”

Each time Kosciuk returns home to California from his transglobal journey, a new series of paintings is born. Last year, The Vault Gallery presented Angels & Orphans, a show of 15 stunning works featuring the children posing with oversized butterfly wings attached to their backs. “That spring before I left for Belarus there were a lot of butterflies outside my window,” Kosciuk explains. “One day the idea came to me: I could put wings on the children. There seemed a certain rightness to it. And I knew the children would flip over them.”

When Kosciuk arrived at the orphanage, the children proved him right—they were eager to don the nylon wings. He posed them near a window, he recalls, and realized that he had unwittingly created a metaphor. “The poor girls seem trapped on the wrong side of the window,” he explains. “I often start photographing the children without an idea in my head, and then something surprising happens.”

In all of his paintings, Kosciuk says that he is trying to capture the children’s beauty, resilience, and strength as well as their vulnerability, fears, and loneliness. “They don’t have a past to draw comfort from,” he says. “And there is no such thing as hoping for an exciting future. Whatever it is, it will be hard. I’m just trying to show them how important they are. I tell them, ‘Someone is paying this much money for a painting of you.’”

By the time this story is published, Kosciuk will be flying back to Belarus, visiting the orphanages once again. Since his fateful trip in 2001, his life keeps getting better and better, the artist says. Among other things, his personal life has taken a surprising turn. During one of his trips in 2004 he met a woman named Tatiana, and they plan to marry in early 2006.

“It blows my mind, what my life has become and what I do for a living,” Kosciuk says. “I will never have regrets about the way I lived my life. Painting used to be who I was. Now it is only a means to support who I am, and the orphans. Who I am and what I do is in Belarus.”

By Bonnie Gangelhoff